sandy nairne

Sandy Nairne, photograph courtesy Tom Miller.

Sandy Nairne (born 1953) CBE FSA was Director of the National Portrait Gallery from 2002-15. Over the course of a 45-year career in museums and galleries he has held positions at Tate, the Arts Council of Great Britain and the Institute of Contemporary Arts as well as working in television and writing. His extensive governance and advisory experience includes roles with St Paul’s Cathedral, Maggie’s cancer care, Courtauld Collection, Seafarers Hospital Society, Clore Leadership Programme, National Trust, Mayor’s Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm, The Wolfson Foundation and the Queen Elizabeth Memorial Committee. From October 2024, he will assume the role of the Chair of the Art Fund.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: Perhaps we can open the conversation with your transition from Economics to Contemporary Art World.

SN: I started at Oxford University focusing on history and economics but got caught up in the contemporary art world. I began by organizing small student exhibitions while at university, and then, at the end of my first year, I went to Edinburgh to work at the Richard Demarco Gallery (RDG) – somewhat by chance.

LŠ: How did you meet Richard Demarco, the contemporary art promoter and former gallerist?

SN: So, Ricky (Demarco) visited Oxford in my first year. He was planning his idea of a summer school which he wanted to stage as part of his gallery programme in Edinburgh in 1972. We met and I got very interested in his vision. Typically of Richard Demarco's spontaneity he just said, very casually: “What are you doing for the summer? Come up to Edinburgh and help." So, I went to Scotland at the end of my first year at college, unsure what he wanted me to do (laugh). But as I arrived; I kind of organically grew into helping with different aspects of the gallery's programme. His gallery was unique in a trailblazing sense - showing the latest avant-garde work from Germany, Yugoslavia, Austria, Poland, Romania, etc.

The gallery was also very much involved in education - long before it became part of wider museum practice - most notably having students from America as part of the summer school. In my first year at RDG, I met the charismatic Joseph Beuys, who was staging his lecture performances (in Edinburgh), which were fascinating - learning about his concept of social sculpture and the links with ecology and the environment. Caroline Tisdale, an art critic for the Guardian, was close with Beuys and helped introduce his work to British audiences.

LŠ: While working for the Richard Demarco Gallery (RDG), I believe you also performed in some art performances?

SN: Well, yes (laugh). I returned to Scotland at the end of my second year at Oxford to help at the gallery as Ricky always contributed to the Edinburgh Festival. Yet, his programme was not part of Fringe - it was independent. The same summer, 1973, the Cricot 2 Theatre from Cracow, created by Tadeusz Kantor, presented a play called: Lovelies and Dowdies. One of the actors had to return to Poland, so everyone suggested I join as I had done some acting at Oxford. I took the part of the Cardinal for the play with a tall metal hat, and my whole role involved holding open a door inside a door-frame and moving around the stage. I was the only British person ever to have the honor of being part of the Cricot 2, albeit briefly.

Sandy Nairne performing in Tadeusz Kantor's Cricot Theatre production of 'Lovelies and Dowdies', Richard Demarco Gallery presentation, Edinburgh, 1973. Courtesy of the curator.

LŠ: Could you describe the art landscape back then in the UK?

SN: Edinburgh was an important scene because of Ricky and his work with Joseph Beuys and many other visiting artists - from Gerhard Richter and Marina Abramović to Gunther Uecker and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Ricky really stood out as an exception in the British art landscape. Prior to that, Edinburgh was known for its rich tradition in theater through the Traverse Theatre and Fringe Festival. Of course, there were many independent and important hubs across the country, from Arnolfini in Bristol, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, and spaces in Nottingham, to name just a few. Newcastle, Manchester, and Liverpool had and still have a rich history of independent visual arts spaces, which I like and admire.

In London, there were many commercial galleries. Nicholas Logsdail opened Lisson Gallery, and Nigel Greenwood had a wonderful gallery near Sloane Square, whose archive is now at the Chelsea College of Arts. Independent figures like Tony Stokes developed a gallery in Covent Garden, which was a very different location in those days before the arrival of all the shops and restaurants. Acme Studios was in an old warehouse space in the 70s where artists did amazing installations. Finally, the ICA (the Institute of Contemporary Arts), initially in Dover Street, moved to its present location in Pall Mall in the 60s and had a long tradition of important shows. The Arts Council England used to run their own exhibition program (across different museums) in addition to being a funding body - until the Hayward Gallery opened. For many years, Tate didn't organize its own exhibitions; rather, they were organized by the Arts Council, which was an unusual arrangement.

LŠ: I wanted to revisit your time at Modern Art Oxford, which was also your first role in the contemporary art world.

SN: The Museum of Modern Art (as it was then called) had no collection but great ambition back then, and the impetus was to make things happen! Nick (Nicholas Serota) arrived in 1973, having worked at the Arts Council before, mostly on their exhibitions - such as a show, The New Art in 1972, introducing important conceptual artists, including Gilbert and George and Richard Long, to a wider audience. I was in the last year of my degree, and he was looking for associates to run the program with. I started in the summer of 1974 and was there until 1976, working on beautiful exhibitions of artists such as Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Howard Hodgkin, Marcel Broodthaers and Paul Neagu.

Sandy Nairne walking through Paul Neagu's Generative Art Group exhibition in the Upper Gallery at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1975.

As a young director, Nick was very adept at finding ways around the limited budget by borrowing from other collections and collaborating with artists directly. Our strategy was that we would do main shows upstairs and use the downstairs of the building for exhibitions focused on education and learning through different partnerships, such as with the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Another factor that boosted the institution's presence was that Oxford was always exciting for the public due to its history and the university. So Nick would invite artists to visit the museum and engage with audiences - long before artists' talks were a regular program element. There was almost no money for the program and we used to make the frames for the artworks ourselves.

LŠ: A curator and woodworker (laugh). After working at Tate in the late 1970s you joined the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London in 1980 as the Director of Visual Arts. Perhaps we could revisit how you wanted to expand the programme?

NS: I left Tate because this period at the end of the 70s was quite complex. The director and the trustees became more conservative, and it was too difficult to get things done. I was excited to join the ICA - there was very little money, but you could actually make interesting shows and support young and emerging artists. Additionally, it had a cinema and theatre, which made it a special place.

My team (including Iwona Blazwick and Steve White) and I tried to shake things up, and the ICA developed a talks and seminars program, which was unusual in the early 80s. We supported radical artists – such as a wonderful project with Stuart Brisley, who made a fantastic performance and installation in the main gallery involving collecting and sorting rubbish, bones and detritus over several weeks. What also excited me was that I could realise projects previously refused. We staged an exhibition titled Women's Images of Men, which was turned down by my predecessor (the art critic Sarah Kent). It was presented in a season with women's performance work, About Time, and an international exhibition selected by Lucy Lippard titled Issue featuring then-young artists like Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, who appeared for the first time in the UK.

Cover of Women's Images of Men catalogue, Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1980. Courtesy Sandy Nairne.

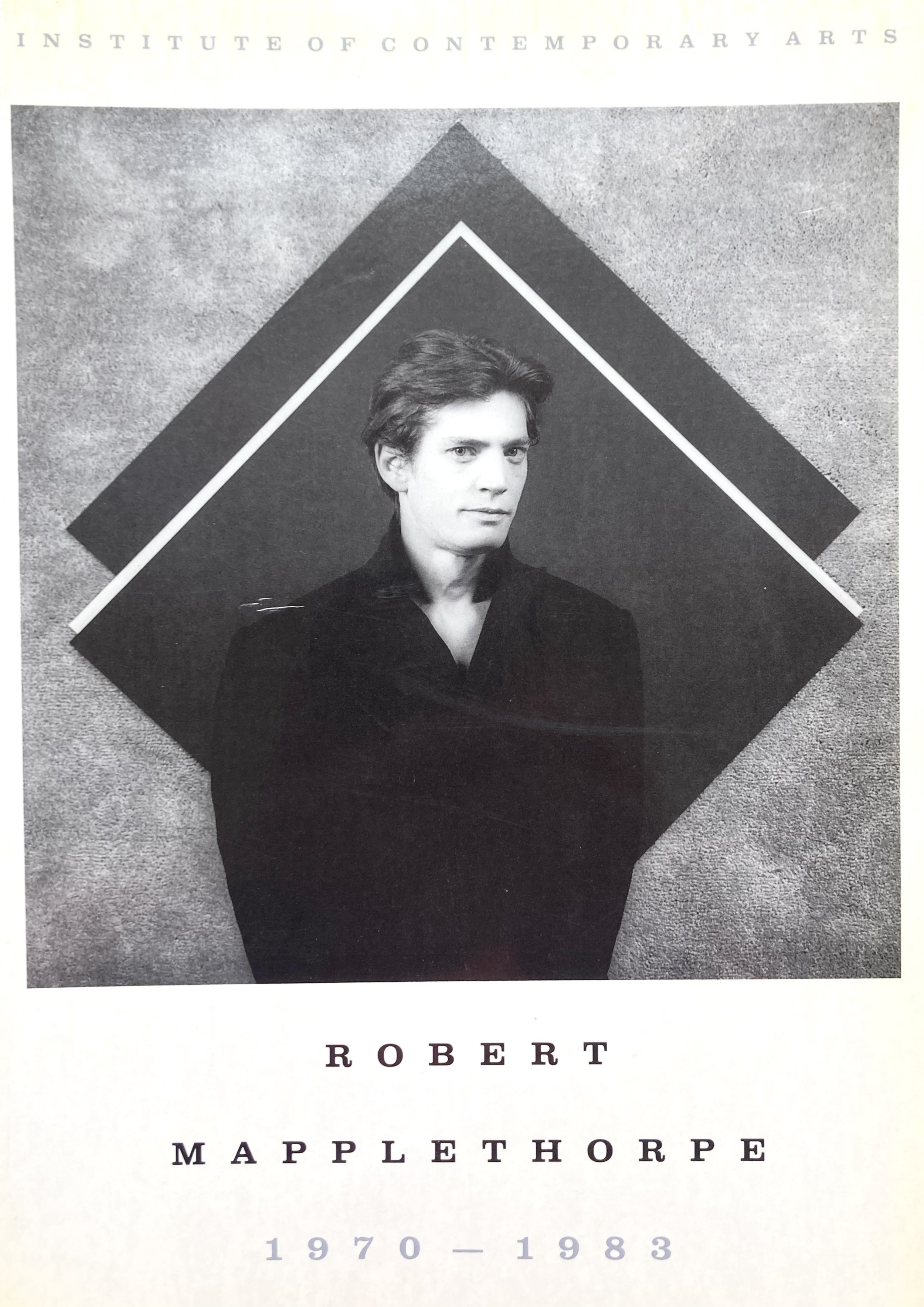

I was also keen on reviving the ICA's strong tradition of working with design and architecture, which had become less active - we undertook a three-year sequence of interventions under the banner of Art and Architecture, with architectural exhibitions and installations – including the American artist Mary Miss reconfiguring the main gallery. It was pretty crazy because, in one year, Iwona Blazwick and I put on 30 exhibitions, including the first retrospective of Robert Mapplethorpe. Each exhibition was for only five or six weeks because we thought everybody who wanted to see it would have seen it by then, and we wanted to do the next thing. We were young and restless. It was ridiculous!

Courtesy Sandy Nairne.

LŠ: After ICA, you turned to television and co-created State of the Art, series which was a major project.

SN: This was in the early days of Channel 4 and I was working with an independent producer, John Wyver. We put together a proposal for a six-hour thematic series about contemporary art worldwide, which would never happen now - you'd never be allowed that much primetime television.

Extraordinary things happened - we recorded the last filmed interviews with Joseph Beuys and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Jean-Michel was fantastic but very hard to pin down because he was so elusive. By the time we were working with him in the mid-80s, he was already very famous - it wasn't long before his tragic death. Trying to film with him was impossible because you could never get a hold of him - no mobile phones or email. In the end, we used to camp out in a cafe near his apartment in Soho and wait for him to come home at one o'clock in the morning to see if we could persuade him to do some filming - which we did. He was very charming. The series was deliberately provocative because I wasn't a presenter - we had all the artists appearing and speaking directly.

Courtesy of the curator.

LŠ: You also worked at The Arts Council England - how did you support the young artists and curators? And how has the organisation changed since your days to today's format?

SN: I moved to the Arts Council (then the Arts Council of Great Britain, as Director of Visual Arts) which had complications with too many directions - from organizing its own exhibitions to education and funding. I thought the Arts Council shouldn't be involved in making exhibitions - it should be left to museums. I was always very critical of this, and saw the Arts Council primarily as a funding and policy body that should support artists and artistic freedom. It was also a big learning curve for me, as I learned a great deal about working alongside the government while remaining independent.

During my time at the organisation in the late 80s and early 90s, it was evident that a younger generation of Black artists was coming through with incredible energy and needed support. I was pleased to be able to support the creation of InIVA (Institute of International Visual Art) through the Arts Council – it has an important mission, vision, and operational model - pushing the boundaries of exhibition-making. Also at that time a young writer called Mathew Slotover came to my office and said he had an idea for a magazine - that would change the publishing game. He was incredibly determined and wanted to call it Frieze. Slotover asked me for initial support, and I arranged for them to get a small grant to start what became the beginning of Frieze.

LŠ: You rejoined Tate at a pivotal moment in the early 90s, when it was expanding to the Tate Modern building on the bank of the Thames. How and why did Tate decide to expand?

SN: Tate's history is complex. However, to give a rough overview of the need for Tate Modern, it is best to summarize. The impetus was that when the Tate was set up in the late 19th century, it was founded as the Tate Gallery of British Art. The National Gallery didn't want to move into the 20th century; they tried to stay out. A similar division exists between the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam. The Rijksmuseum sits at a certain point, and then after that point in time, you've got the Stedelijk (for modern and contemporary). Right up until the 1950s, the Tate Gallery was organised as a subsidiary of the National Gallery - it was not independent.

For part of the inter-war period, the Courtauld (today the Courtauld Gallery in London) was also part of this history, as Samuel Courtauld's collection was on loan to the Tate. There's an amusing moment when the young Alfred Barr, just as he is becoming director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, visits London. He goes to the Tate and sees all these Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings - thinking how impressive London's public collections are. But all the paintings he saw belonged to Samuel Courtauld, not the nation - they were essentially still a private collection. Courtauld would eventually set up what is now the Courtauld Gallery as a separate museum - leaving a huge gap in Tate's collection.

Nick (Nicholas Serota, the then director of Tate museums across the UK) and the trustees knew that to expand the modern collection of Tate you'd need collectors in Britain who had those works and would be willing to give them to the nation. Tate Modern as a concept was the beginning of how to think differently about what international meant in the London and UK context. And we needed a space to reflect this! In a way what was outrageous about the project was creating another national museum in London because the government was always saying you must do new things outside London. Every government thinks that there are too many institutions in London!

But it was Nick Serota and the Tate trustees who raised the funds because the government wasn't supportive at the beginning. I was still closely in touch with Nick and knew his ambitions - and why Tate Modern was so important for London as one of the major international arts centers. I also knew that if this ambitious plan of his might happen, it would create a vital international opportunity for British artists - whom we wanted to support. So, I got involved at the start by co-creating the MA in Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art because I was apprehensive that there wouldn't be enough curators if Tate succeeded in expanding.

LŠ: It would also be great to learn more about how the collection and exhibition programme at Tate Modern was formed.

SN: The great thing about Tate Modern was its work as both a theoretical and practical exercise - about how the building might be used and its options for display. Lars Nittve was appointed as the first director in 1998. However, the two vital people thinking about the displays were Frances Morris (who later became director of Tate Modern) and Iwona Blazwick (then working at Thames & Hudson and later director of the Whitechapel Gallery). Frances and Iwona developed a set of workshops on how to create collection displays and new exhibitions - and listening to them was fascinating. Some critics pointed out that the Tate Modern collection was not strong enough: it doesn't compare with New York, or even arguably with Berlin, and certainly not with Paris. So, if you stuck with conventional chronology, it would not look very good. Frances and Iwona made the whole display programme dynamic by being thematic and not chronological.

LŠ: As you also ran the National Portrait Gallery - how do you see the current landscape of arts London and around the country? The museums have, for example, faced a cut in funding from institutions such as the Arts Council, and artists are struggling with the incredible rise in living costs, to name just a few of the serious challenges.

SN: It's a very big question; the clear and perhaps only answer is that it's tough. What makes me optimistic about the UK - not just London - is this huge shift in the showing of art. When I was talking earlier about the situation in the 1970s or even into the 1980s, financially, it was very hard. But out of these hardships, centres in Gatehead such as the Baltic, or Fruitmarket in Edinburgh, or Turner Contemporary in Margate, have emerged, adding to the conventional civic galleries and important university collections such as Kettle's Yard in Cambridge. It's still tough!

Although there is a lot of pressure on artists and institutions, I take great hope in the innovation of artists and their incredible ability to create opportunities. If you don't have artists coming up and exchanging ideas with their peers - the scene will die. Thus, we must support artists. The current arts scene (taking out of the equation the commercial art world) in London and around the country is reminiscent of the 60s and the 70s - very self-reliant and independent. Another critical part for going ahead is trust - just on institutional level - without it you cannot create international exhibitions as no one will lend you valuable works of art.

We also need to include more people. I am not sure whether there's been enough shift in terms of cultural power - is it all still too white and male? I'm now 70 years old, and my generation tried to support change in the composition of who's leading activities across the arts scene - but I'm sure that more needs to be done.

What worries me is that London, like most big cities, has terribly complex property pressures and prices. It's horrible! I'm confident that museums and galleries have their place and will develop, however I'm less confident about some of the strains and difficulties for artists coming through in the next generations. In this sense, I am very supportive of the efforts by the Mayor's office - initiatives in London to support studio blocks and facilities. In current times, it is crucial work!