KARIM RASHID

Courtesy of Karim Rashid Inc.

Visionary and prolific, Karim Rashid is one of the most unique voices in design today. Eschewing style in favor of designing in the modus of our time, Karim work encompasses more than 4000 designs in production, 400 awards to his name, and clients in 47 countries. His clients include 3M, Alessi, Artemide, BoConcept, Citibank, Hugo Boss, Issey Miyake, Kenzo, Method, NH, Radisson Hotels, Umbra, Veuve Clicquot, and Vondom. Numerous awards and accolades including the American Prize for Design Lifetime Achievement award, Red Dot award, Chicago Athenaeum Good Design award, and Pentaward attest to Karim’s contribution to the world of design.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: Your design path has left a significant impact on the whole design community as well as how we view everyday objects. Certainly unique was also your educational path having studied under the Memphis founder and design legend Ettore Sottsass. How do you see his teaching and practice shape your approach to design - specifically, how did Sottsass’s approach to color, form, and functionality influence your design language?

KARIM RASHID: Studying under Ettore Sottsass was a transformative experience that profoundly influenced my design approach. Sottsass's emphasis on bold colors, geometric forms, and experimentation with materials encouraged me to push boundaries and challenge conventional design norms. His approach to design as a vibrant, holistic, multidisciplinary practice also resonated with me. Most importantly I feel he had a beautiful aesthetic eye and believe everything in our lives should be beautiful, proportional, and aesthetic.

Bounce Chair/Gufram, 2014.

Superblob/Edra,2002.

Klean Dishrack/Guzzini, 1999.

Sketch, Superblobs, 2003.

Sketch, Chairs, 2011.

100 pieces Bench sketch, 2010.

LŠ: Whose design philosophies do you admire and why?

KR: Growing up, I was influenced by many artists, architects, and designers. From Russian constructivism to the Bauhaus, from Yves Saint Laurent to Jean Couregges and Pierre Cardin, from Joe Colombo to Luigi Colani, from Le Corbusier to the De Stijl movement. I admired multidisciplinary designers like Raymond Loewy and Andy Warhol, and visual creatives like Jean-Paul Goude and Hypnosis and Hardie. The design philosophies of Dieter Rams and Alessandro Mendini also align with my design values.

Karim’s parents - Joyce and Mahmoud in Paris, 1957.

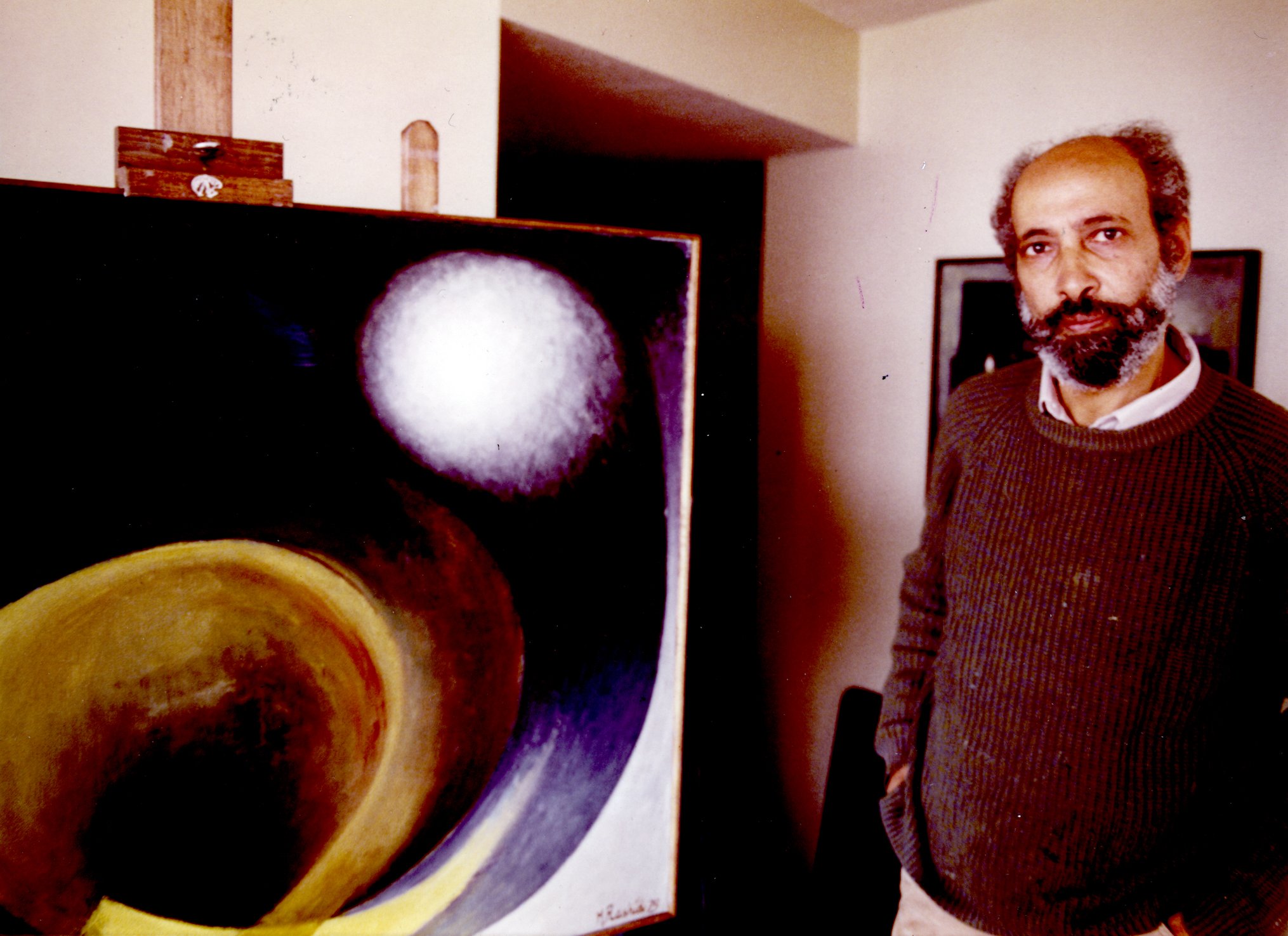

Mahmoud Rashid in Studio in Toronto, 1970.

Karim with his brother Hani in their home in Mississauga, Ontario, 1970.

LŠ: Speaking of the design philosophies, the design world has seen incredible shifts in recent years. Moving forward, what skills and knowledge do you think designers should develop? What tools and new approaches do you think design schools should consider given how drastically the field of design is altering?

KR: As the design landscape continues to evolve, I believe designers should develop skills in:

1. Function - I stress the importance of functionality, as design has shifted from a responsible, functional approach to post-modernism, where it's only visual, and we forget that design is for us, hence design must be seamless and work perfectly.

2. Sustainability and environmental responsibility

3. Emerging technologies like AI, AR, and 3D printing

4. Human-centered design and empathy

5. Interdisciplinary collaboration and communication

6. Business acumen and entrepreneurship

7. Originality - we're seeing non-stop similarity and copies.

Design schools should incorporate these topics into their curricula and provide students with hands-on experience through projects and collaborations with industry partners.

Lotus/Tonelli, 2005.

LŠ: Following your studies, you stayed in Italy and worked at Rodolfo Bonetto Studio. What projects did you work on? Also, could we revisit the Milan design scene of that time - as you experienced it? What are some of your fond memories of the city?

KR: During my time at Rodolfo Bonetto Studio, I worked on various projects, including furniture and product design. Notable projects included designing a television for Brionvega, dashboards for Fiat, and products for Guzzini, an Italian manufacturer of plastic tableware. The Milan design scene in the 1980s was vibrant and dynamic, with a strong emphasis on innovation and experimentation. I have fond memories of attending design events, visiting showrooms, and experiencing the pop-cultural milieu, from Italodisco to new-wave fashion and design.

Karim with Pauline Landriault, Ottawa, 1980.

Karim in Ottawa, 1981.

Karim in Milano.

Aura Table/Zeritalia, 1995.

LŠ: You’ve spoken about ‘democratic design’ and making design available to all. What does democratic design mean to you today and which of your projects do you feel best embodies the idea of democratic design - and why? How do you balance this commitment with the commercial realities of the industry and have you ever faced resistance from clients or manufacturers in the implementation of these principles?

KR: Democratic design is about making design accessible and affordable for everyone. I balance this philosophy with commercial realities by working with clients and manufacturers who share my values. While I've faced resistance from some clients, I've also collaborated with like-minded companies prioritizing accessibility and sustainability. The Oh Chair from 1998 embodies democratic design principles, with its simple, ergonomic design and affordable price point making it accessible to a wide range of consumers. Over 3 million have been sold.

Oh!Chair/UMBRA, 1998.

Skinny Can/UMBRA, 2011.

Garbo/UMBRA, 1995.

LŠ: You often spoke of your fascination and work with plastics as a material. Why was it so fascinating to you from the start and how has your view of the material changed to date? Also, given much discussion and criticism the material is experiencing - how do you see its future in a world that is increasingly turning towards sustainability?

KR: I've always been fascinated by plastics due to their versatility, durability, and potential for innovation. However, I'm aware of the environmental concerns surrounding plastics and have always considered this issue since my education in Canada emphasized the importance of a product's entire lifecycle. As designers, we must consider the ecological impact of our materials and explore sustainable alternatives.

For the past decade, I've encouraged manufacturers to use bio-plastics or perfectly recyclable polymers. As a child, I was inspired by beautiful, inexpensive objects made from bright, colorful plastics. We cannot live without plastic, but the real issue is that recycling is not taken seriously by governments, so we need better legislation. Globally, most plastics are not recycled. Many companies are responsible for making this change, especially those involved in food packaging and daily disposables, which are the worst offenders due to a lack of infrastructure for recycling.

Blob Lamps/Foscarini, 2002.

Dish and Hand Soaps/Method, 2004.

Kurl Shelf, Zeritalia, 2003.

LŠ: As you moved back to Canada, what differences did you notice in the design culture compared to Italy - why do you think there was a different attitude?

KR: Upon my return, I noticed a more subdued and conservative design culture. However, this difference allowed me to establish my unique design voice and approach. Establishing my studio in NYC in 1993 was a natural progression of my career. I felt that, at 33, I had learned enough and was ready to maintain creative control and explore projects aligned with my design philosophy.

Karim installing post box for Canada Post, 1987.

LŠ: What were some of your favorite early projects and why?

KR: In Toronto, I worked with many companies, designing power tools for Black and Decker and Toshiba, to create democratic objects. This experience led me to coin the term "Designocracy." One of my favorite early projects was designing a modular furniture system for Canadian manufacturer Nienkamper, titled Wavelength. This project taught me the importance of scalability, modularity, and collaboration with industry partners. Working with Umbra, Nambé, and others taught me about production and scalability.

Wavelength Bench/Nienkamper, 2002.

LŠ: You worked with numerous fashion companies- what were some of the most surprising things you learned from collaborating with fashion designers like Issey Miyake and Giorgio Armani?

KR: Collaborating with fashion designers like Issey Miyake and Armani was an incredible experience. I learned about attention to detail, craftsmanship, and the emotional connection between users and products from Armani.

Pour Homme, 2 in 1/Issey Miyake, 2003.

Mother’s Day Gift Pack/Issey Miyake Women, 2002.

Amore/Kenzo, 2004.

Karim for Prescriptives, 1999.

LŠ: With new technologies being introduced in recent work - which ones are shaping your work the most? How do you think technologies like AI or 3D printing will change the role of the designer?

KR: Design should be a mirror of the day in which we live and hence if you design in the ziegiset of the time you live in, meaning embracing software, technologies, social behaviors, then you will touch and evolve and progress humanity.

Magino Stool and Table/UMBRA, 2007.

Koochy Sofa/Zanotta, 2007. All images are courtesy of Karim Rashid Inc.

New technologies like AI, AR, and 3D printing are revolutionizing the design industry. These tools enable designers to create complex shapes, simulate user experiences, and prototype ideas more efficiently. As designers, we must adapt to these technological advancements and explore their potential applications. The future of design will involve the seamless integration of technology, sustainability, innovation, and human-centered design. Design doesn't need to exist and objects and spaces do not need to exist unless they provide us with a better life.

Karim with his wife, Kiana Ahmadi Rahmatabadi.