GEORGE NAKASHIMA

Mira and George Nakashima, circa 1973. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

George Katsutoshi Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington, in 1905, spent the most meaningful moments of his life in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, majored in Forestry at the University of Washington before switching to Architecture and graduating in 1929. He received a scholarship to the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Fontainebleau, France, in 1929, and received a Masters in Architecture from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1930. During the Great Depression, he sold his beloved car and bought a steamship ticket around the world, eventually joining the Architectural Office of Antonin Raymond in Tokyo in 1934. The Raymond Office sent him to Pondicherry, India in 1936, to build the first reinforced concrete building on that continent for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, where he became a disciple in 1938 and was given the name “Sundarananda” he who delights in the beautiful.

However, because of the War, he reluctantly returned to the USA via Japan, where he met Marion Sumire Okajima, married her in Los Angeles in 1941 and moved to Seattle to begin his furniture business. With his family, he was incarcerated in Camp Minidoka, Idaho in March of 1942, where he apprenticed to a Japanese carpenter named Gentaro Hikogawa. At the request of his professor at MIT, Noemi and Antonin Raymond sponsored Nakashima to work on their farm in Pennsylvania in 1943. He decided to make his home in New Hope, bravely re-starting his furniture business from scratch on land bartered for labor while the family lived in a tent and continued to landscape and build on the hillside property. At the introduction of Antonin Raymond to Hans and Shu Knoll, Nakashima worked alongside Harry Bertoia, Isamu Noguchi and Buckminster Fuller to create designer chairs, cabinets and tables in the 1940s. He later designed furniture for the Widdicomb-Mueller company in the 1960s, and taught furniture design at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India in the 1970s. In 1964, he established a friendship with the Minguren group of craftsmen at Sakura Seisakusho in Shikoku, Japan, thereby producing 7 shows in Tokyo during his lifetime, and passed that collaboration on to the next generation.

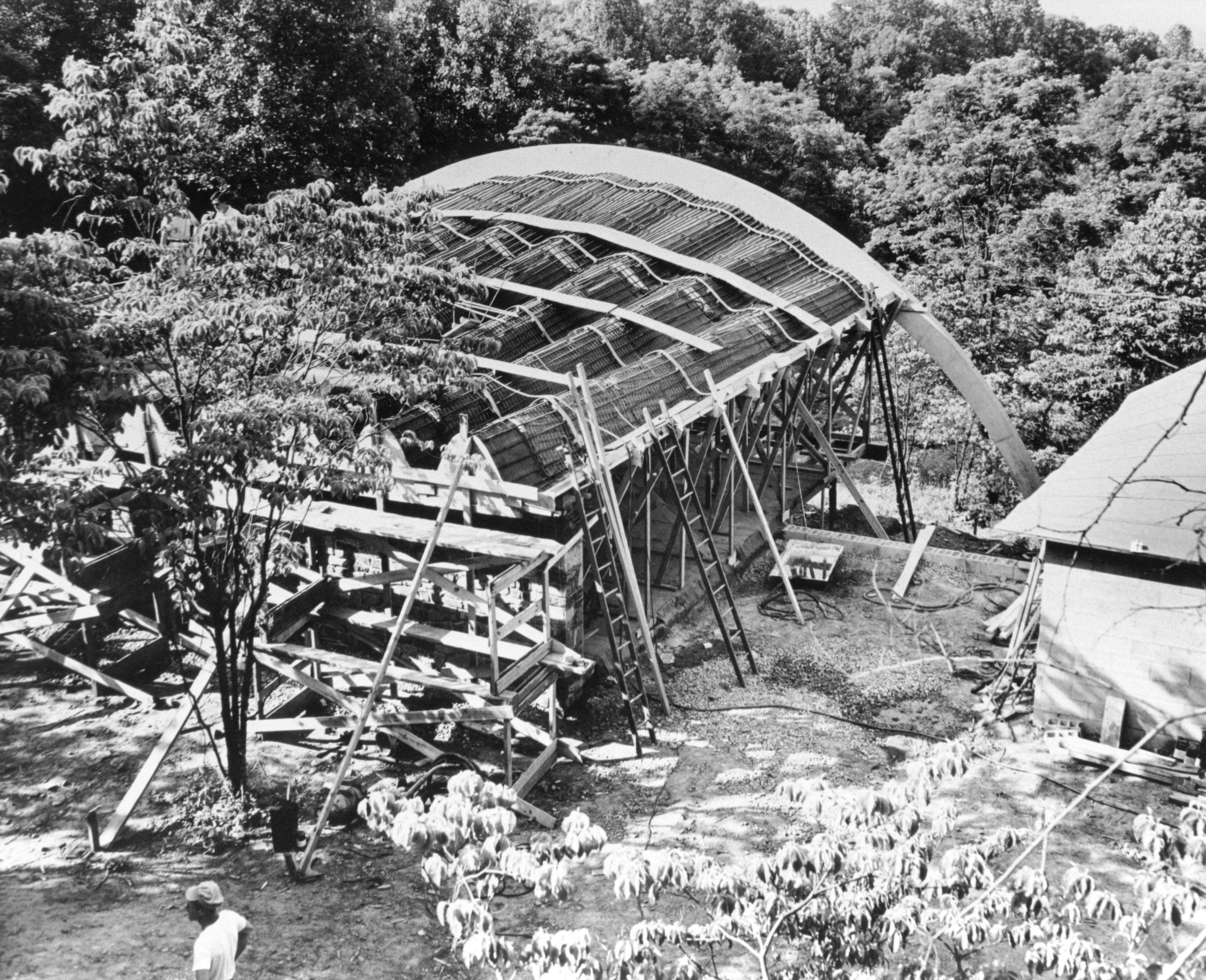

George Nakashima was perhaps one of the first furniture designer/craftsmen to use butterfly joints as a decorative way to secure cracks, as well as to revolutionize the term “free-form” to mean retaining the natural contours of flitch-cut timbers. He wrote and published a book “The Soul of a Tree” in 1981 which continues to inspire generations of woodworkers. He won many awards, including the Third Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Emperor and Government of Japan in 1983, and had his first/last retrospective show at the American Craft Museum (now MAD) in 1989. Although he left architecture as a profession, he designed and built over 15 buildings on the Nakashima property, seven with warped thin-shell roofs; he also designed and built a reinforced concrete Hyperbolic Paraboloid roofed church in Kyoto in 1965 plus two unusual adobe chapels in New Mexico (1972) and Mexico (1975).

Nakashima passed away in 1990, leaving behind a massive collection of custom-milled hardwood lumber which still sustains his furniture business under the guidance of his daughter Mira, who apprenticed under him for 20 years.

Mira Nakashima was born in Seattle in 1942, incarcerated in Minidoka, Idaho during the war, and raised in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where her father, George Nakashima, established his studio. She earned a Bachelor of Arts from Harvard (1963) and a Master of Architecture from Waseda University, Tokyo (1966). After raising a family in Pittsburgh, she returned to the Nakashima Studio in 1970, apprenticing under her father until his passing in 1990, when she became creative director.

Mira contributed to exhibitions such as Full Circle (American Craft Museum, 1989), The Soul of a Tree(Japan, 1993), When Nature Smiles (Tenri Gallery, Soho, 1994), and The Modernist Moment (James A. Michener Museum, 2001). Her solo shows include Keisho (Moderne Gallery, Philadelphia, 1998) and Shoki (Moderne Gallery, Philadelphia, 2009). She authored Nature Form and Spirit (Harry N. Abrams, 2003) and curated exhibitions like the Redwood root burls show (New York, 2006), Craft in America(PBS series, U.S. tour, 2007–2009), and Nakashima Looks (James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, 2019). She also launched a rug line based on Nakashima designs (Tai Ping/Ed Fields, 2015) and collaborated on installations worldwide.

Mira has continued her father’s dream of building Peace Altars, with installations at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine (New York, 1986), the Russian Academy of Art (2001), and Auroville, India (1996), and is working on a fourth. In 2014, the Nakashima property was designated a National Historic Landmark and added to the World Monuments Fund List. She has expanded George’s legacy by producing his classic designs, reviving older pieces, and creating new works.

LUCIJA ŠUTEJ: What were some of the design philosophies and techniques that your dad passed on to you?

MIRA NAKASHIMA: He never spoke. I don't know if you know of the book by Soetsu Yanagi called "The Unknown Craftsman," translated by Bernard Leach of the Mingei Arts Movement. I didn't read that book until I was getting ready to write my book in 2003 after my father died. His philosophy seemed so similar to my father's. One of the things he said is that artists don't talk, so dad never spoke to me. I learned what I learned mostly from the men in the shop because I was working with them. When I finished my office work, I got to work in the shop. The only thing I learned from dad is not to question authority. He wanted to be in full control of everything. It was not exciting because it's always hard working for your family.

Process of grass seated chair. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Nakashima at work in his old shop on Aquetong Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: How did you experience the evolution of your father’s work as you became an important part of the design team?

MN: Dad's process was very similar to Yanagi's approach - you have an idea that manifests itself through production. When I joined the team, my father was no longer working in the workshop. He was working through the men -supervising everything everybody made.

My father would give instructions to the team through really sketchy drawings. He had little pieces of paper and he would create freehand sketches of perspectives with a few dimensions. When I joined in 1970, following my architectural degree from Harvard University, I would always suggest we use dimensions and scales and my father always said of his team, "They know how to do it." (laugh) And actually, they were very well-versed in reading his drawings as he trained them. Also, he was on site in the shop every single day, so he could guide them and help.

Conoid Studio Construction, Aerial angle. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Conoid Construction in 1957, George pictured with Kevin. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: Would you publish a book of his sketches?

MN: No, because my father’s shop drawings were on these little pieces of paper that the team would throw away as they finished projects. We saved a few, but the practice back then was different. Now we think those drawings are precious, but everybody just used them and threw them away. We save our drawings now. They're not as beautiful as dad's, but we keep them for reference.

LŠ: Nakashima studied architecture at Harvard University and MIT, and lived in Japan and India - how did these experiences shape his outlook on the field?

MN: Actually, he first went to the University of Washington majoring in Forestry- because he loved trees. He was brought up in the Pacific Northwest and did a lot of hiking and camping. He switched to architecture and did well. When he joined Harvard, they were more interested in the Bauhaus tradition, focused on shapes and forms rather than construction and actual building. So he decided to switch to MIT because they were more oriented towards engineering and actual projects.

My father graduated during the Depression and at some point he decided to sell his car and buy a steamship ticket around the world, staying in Paris for a while, where he was one of the starving artists. He saw Couvent de La Tourette under construction and was fascinated by reinforced concrete. Gothic cathedrals, particularly Chartres, left a big impression. Not solely the aesthetics, but the technology and collaborative nature of building - how people from all walks of life worked together to honor God.

George Nakashima in Seattle, 1920s. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

In 1934, he arrived in Japan, where my grandfather instructed him to get a real job (laugh), he started working for architect Antonin Raymond’s Japanese projects. In Japan, they relied heavily on the daiku -the Japanese carpenters, who knew how to do everything traditionally, passing on the knowledge of wood construction engineering from generation to generation.

Following his time in Japan, he was sent to India with Raymond's office, where he was supposed to build and supervise the first reinforced concrete building on the continent. Nobody had done it before, so he had to train the workmen and figure out how to build the formwork. All the formwork had to be precise but because he initially worked with mango wood which didn't stay flat, he later switched to teak.

LŠ: Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, was that his first time in Japan, or did he visit before as a child?

MN: He had gone once in his early 20s with my aunt Mary when she was still in high school. The next time was with me in 1964, when he tried to give a talk in Japanese at Waseda University but had to switch to English because he was out of practice.

When he lived in Japan, he was primarily in Tokyo, but his best friend architect Junzo Yoshimura (from the Raymond office) took him to Kyoto and Nikko. Dad was particularly impressed with the Katsura Detached Palace, which Bruno Taut also considered important. He admired the abstract way spaces were put together, the relationship to the outside and landscape, and the flow of air, space, and light.

LŠ: Did he meet with any other Japanese contemporaries such as Kenzo Tange or other members of the Metabolist movement? Perhaps also with the founder of the Mingei movement and critic Soetsu Yanagi?

MN: I don't know. The only ones I've heard about are the architects from the Raymond office in the '30s. Like you, I'm curious whether he met Soetsu Yanagi and the Mingei movement. Another person I wonder about is Charlotte Perriand, who was in Tokyo around the same time as my dad. There are similarities in their design approach, but I don't know if they ever met.

Raymond and Associates. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: Why did Nakashima decide to leave architecture and move to the field of furniture design?

MN: After returning from India and Japan in 1940-41, he decided to survey the architecture built on the West Coast while he was away. He was shocked at the shoddy workmanship. He saw a Frank Lloyd Wright building under construction and decided not to do architecture anymore. Dad said in American architecture they would just bang two-by-fours together with nails. After studying beautiful joinery in Japan, he couldn't accept that they were essentially building stage sets, looking beautiful on the outside but poorly constructed inside.

George in first workshop on the current site. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Nakashima’s Conoid studio. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

George with daughter Mira in the shop, 1952. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: We talked of your father’s time in India, when and how did your father meet fellow architect and designer Gira Sarabhai?

MN: It was in 1964, that he went to India with me because he was supposed to go to NID (National Institute of Design) and meet Gira (Sarabhai) to discuss teaching there. In the end, he taught at NID for about six years, going over every other year to teach a class for about a month. There's been a proliferation of rosewood chairs still made in India - basically the same design as the grass-seated chair we make here. Dad taught them how to make them.

The students did full sets of drawings for the pieces they made. When he came back home in New Hope, he wasn't doing detailed drawings of all the furniture, but the NID students did. He designed several pieces for them to manufacture - chairs, including a version of a Mira chair, round tables, and square tables. They would sell these to support the school.

LŠ: How did his time in India shape his approach to design principles?

MN: Working with Sri Aurobindo and the Mother of Ashram on building Golconde Dormitory was both a major exercise with reinforced concrete in a country unfamiliar with it and spiritual training. He worked with other craftsmen, including an architect named Samer and an engineer named Udar.

George in India ca. 1937. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Nakashima at Sri Aurobindo Ashram ca 1936. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

He always carried a small blue notebook where he would write questions for the Mother, and she would respond. Once, he came into conflict with another worker, and the Mother said it was unacceptable. This taught him about sublimating ego - similar to building cathedrals in France. It wasn't about personal expression but working toward a higher purpose. Sri Aurobindo gave him the name Sundar Ananda, meaning "he who delights."

When I worked with my dad from 1970-1990, we would always have open houses on Saturday afternoons. Dad would often give clients his anti-ego lecture. He was on a mission - Western culture's emphasis on ego was contrary to the ashram's teachings.

LŠ: And when did your father first learn the different Japanese joinery techniques?

MN: In Japan, he learned about joinery but didn't work alongside carpenters - he supervised them. However, during WW2 we were in an internment camp where the conditions were difficult. My mother struggled - I was six weeks old, and it was hard to find formula. Luckily, friends would drop off care packages.

When Executive Order 9066 went out, our family coordinated to be in the same camp in Idaho. My mother's father and sister came from California, and my dad's relatives came from Portland and Seattle. The barracks were built hastily in isolated desert areas on Native American land. Dad said they were "boards and battens without the battens" - wall boards with spaces between them. It was desert - cold at night, hot during the day. Initially, dad used his old blueprints to cover the walls and keep out the wind.

There, he worked with a Japanese carpenter, Gentaro Hikogawato, to make the living spaces more habitable. They used leftover building materials and collected bitterbrush (desert shrubs) from outside. While most used it for firewood, dad and Gentaro saw their beautiful shapes. They'd peel the bark, and sand and shape it into decorative pieces. Dad was grateful to work alongside such a highly trained carpenter, exchanging ideas and techniques and learning different joinery techniques.

LŠ: How long was your family there?

MN: We entered in March 1942. Antonin Raymond, dad's boss from Tokyo who had settled in Pennsylvania, and dad's MIT professor helped sponsor our release. The Raymonds petitioned for us, offering my father work as a chicken farmer since he couldn't work on their government projects related to the war effort in Japan. We arrived in Pennsylvania in September 1943, after about 18 months. Everyone else remained for almost three years. The Japanese Americans were resourceful - they planted gardens to supplement the expired army rations and learned to survive in the desert.

LŠ: With your family’s move to Pennsylvania - step by step you built your lives there. These experiences and circumstances naturally also shaped the cornerstone of Nakashima Furniture. Your father’s designs are known for using butterfly joints. Could you tell us more about why he chose that technique?

MN: The butterfly joint is strong and simple. If a board has a big crack, a butterfly joint will stop it from cracking further. If you have two separate boards, it’s a very stable way to join them.

Dad might have learned about butterfly joints in Japan or even during his time at the Minidoka internment camp. They’ve been used for centuries in Europe and Japan. In Europe, they were hidden under veneer, and in Japan, they were covered with plaster on walls. But dad saw the form as beautiful and decided it should be visible. He made it an integral part of furniture design. When done well, with skill and good wood, it’s not just functional—it’s art.

Following his time in Japan and India, my father wanted to make his butterfly joints out of rosewood or laurel. But he didn’t have any, so he went to a lumber broker in Philadelphia. Dad showed up in his old overalls and asked if they had any rosewood or laurel. (laugh) The broker just said, “Oh no, that’s too expensive. We don’t sell that.” In the end, he gave my father old reject logs as he was trying to get rid of them.

Dad went down to the sawmill and spent the whole day figuring out the best thickness for cutting the reject logs. Bob Thompson from Thompson Mahogany Company helped us treat the logs by air-drying and kiln-drying the lumber. He did that for my father’s entire life. Without Bob and his company, we couldn’t have done what we did.

Mira with her father at the rented farmhouse on Aquetong Road, circa 1946. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: I read that your father preferred oil finishes to protect the wood. Why was he so drawn to oil instead of material like lacquer?

MN: He believed wood was still alive, even after it was cut into planks. It moves—it absorbs moisture when it’s humid and shrinks when it’s dry. With oil finishes, the wood can breathe, expand, and contract naturally.

Oil also brings out the depth of the grain. We apply four or five coats of oil, sanding between each coat with increasingly fine sandpaper. It’s a long process, but it creates a smooth finish that enhances the grain. People often ask, “How do you get the wood so smooth?” Well, it’s weeks of oiling and sanding!

Home construction ca.1947 . Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Dining room and kitchen at home. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Home exterior, 1948. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Home front view. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

George with wife Marion and daughter Mira at home, circa. 1948. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

LŠ: Did your father ever collaborate with other artists or architects, like Buckminster Fuller or Harry Bertoia on his furniture designs?

MN: He didn’t collaborate much. He liked doing things his way. He was friends with Harry Bertoia and traded furniture and sculptures with him. He also worked with Ben Shahn—dad designed and furnished the second floor of Ben’s house, and Ben gave us some artwork in return, including a mosaic on one of our walls.

But no, he didn’t collaborate on projects with Bertoia or Bucky Fuller. They might have discussed ideas, but nothing concrete came out of it.

LŠ: In today’s world of automation and AI, what lessons should young designers take from your father’s work?

MN: Dad believed human hands, eyes, and natural materials should be respected and honored—not forgotten or replaced by technology. When you work on a screen, it’s always two-dimensional. But when you work with your hands, it’s different—it’s three-dimensional, tactile, and alive.

Nakashima believed natural forms should be celebrated. I hope young designers don’t lose sight of that.

Home Interior. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Home Interior, January 1948. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Home, Mira’s room. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.

Undated color photograph of Mira and Early Tables. Courtesy: Nakashima Foundation for Peace, New Hope, PA.